Recently I've been posting from Instapaper directly to my blog (and thence to Facebook). But the newest version of the Instapaper app has a bug that prevents me from doing that. So here's a roundup of some recent stories I've enjoyed. -Egg

14 reasons why this is the worst Congress ever

Technology Provides an Alternative to Love. - NYTimes.com

STANFORD Magazine: March/April 2010 > Features > Clelia Mosher

Search This Blog

Saturday, July 14, 2012

Amazon reviews for creepy Olympic mascots

[Charlie Stross]

The Blitz spirit:

To all those of you who live in London and are having to put up with the current Olympic insanity, I send my condolences.

For those of you who don't, to give you some idea of the sheer cognitive weirdness of LOCOG (who, I swear, could keep a psychiatrist working on new diagnoses to add to DSM-VI for a decade), here's one example of how London (and the UK in general) is responding to these neo-fascist killjoys.

See, the Olympics have two cuddly toy mascots, Wenlock and Mandeville. (Never mind, for now, that these focus-group-tested horrors resemble a bizarre cross between an animated CCTV camera and a dildo with legs: it's the thought that counts.)

Of course, as is always the case with sporting mascots these days, merchandising happens: toy plushies are on sale. And so are much more dubious souvenirs. ("Hello, I'm Wenlock! Don't I look smart in my police officer's uniform? I have the important job of protecting you on your journey to the London 2012 Games ... we can have lots of fun together!")

No, seriously: go marvel at the true Orwellian horror of the product, then read the customer reviews. Especially the one-star reviews.

The Blitz Spirit is still alive and screaming and on display inside Amazon.co.uk's reader feedback!

(Final note for LOCOG rights gestapo: I do not consent to the idiotic terms of use that I have been informed can be found at the other end of that link. If you object to this blog entry, feel free to piss up a rope.)

The Blitz spirit:

To all those of you who live in London and are having to put up with the current Olympic insanity, I send my condolences.

For those of you who don't, to give you some idea of the sheer cognitive weirdness of LOCOG (who, I swear, could keep a psychiatrist working on new diagnoses to add to DSM-VI for a decade), here's one example of how London (and the UK in general) is responding to these neo-fascist killjoys.

See, the Olympics have two cuddly toy mascots, Wenlock and Mandeville. (Never mind, for now, that these focus-group-tested horrors resemble a bizarre cross between an animated CCTV camera and a dildo with legs: it's the thought that counts.)

Of course, as is always the case with sporting mascots these days, merchandising happens: toy plushies are on sale. And so are much more dubious souvenirs. ("Hello, I'm Wenlock! Don't I look smart in my police officer's uniform? I have the important job of protecting you on your journey to the London 2012 Games ... we can have lots of fun together!")

No, seriously: go marvel at the true Orwellian horror of the product, then read the customer reviews. Especially the one-star reviews.

The Blitz Spirit is still alive and screaming and on display inside Amazon.co.uk's reader feedback!

(Final note for LOCOG rights gestapo: I do not consent to the idiotic terms of use that I have been informed can be found at the other end of that link. If you object to this blog entry, feel free to piss up a rope.)

Friday, July 13, 2012

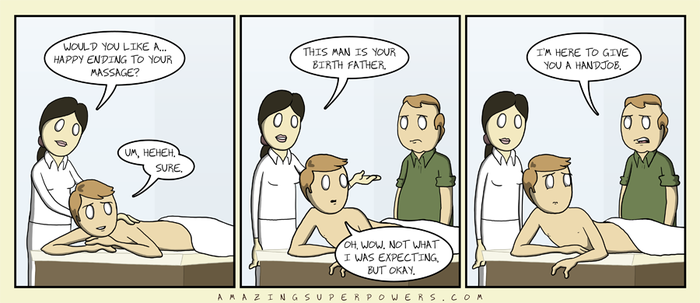

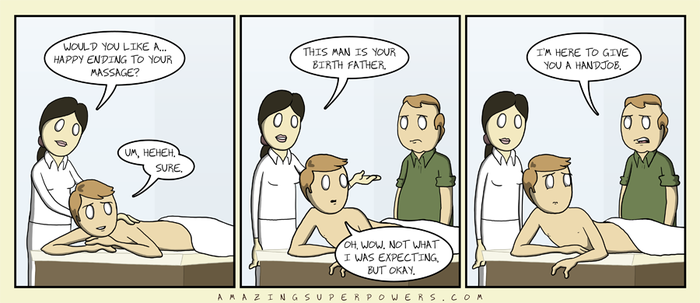

Happy Ending

Happy Ending (No Comments):

And here’s a comic built for a Friday. Enjoy your weekend. It could be your last! Maybe!

And here’s a comic built for a Friday. Enjoy your weekend. It could be your last! Maybe!

Thursday, July 12, 2012

Apply Truth Goggles, learn truths

[What an *amazing* idea (although not ready for prime-time). -egg]

Apply Truth Goggles, learn truths: Truth Goggles is a web app that highlights facts in the text of a web page or news story and provides a link that tells you whether or not those facts are true.

Apply Truth Goggles, learn truths: Truth Goggles is a web app that highlights facts in the text of a web page or news story and provides a link that tells you whether or not those facts are true.

Stories from the world's first sex survey

[Fascinating. -egg]

[Boing Boing]

Stories from the world's first sex survey:

This woman, Clelia Duel Mosher, conducted the world's first sex survey—a series of interviews with 45 American women, most of whom were born before 1870. She conducted the surveys off and on between 1892 and 1920, but never published on them. They were found in 1973, and present an interesting take on Victorian and Edwardian-era women's sex lives, something we usually only hear about from decidedly biased sources from that time period that often claim women didn't like sex at all.

The surveys show that wasn't the case. More interestingly, they tell the story of changing expectations about marriage and sex.

Read more about the survey and Clelia Mosher in the Standford Alumni Magazine.

Thanks to Jennifer Ouellette for linking to this story!

[Boing Boing]

Stories from the world's first sex survey:

This woman, Clelia Duel Mosher, conducted the world's first sex survey—a series of interviews with 45 American women, most of whom were born before 1870. She conducted the surveys off and on between 1892 and 1920, but never published on them. They were found in 1973, and present an interesting take on Victorian and Edwardian-era women's sex lives, something we usually only hear about from decidedly biased sources from that time period that often claim women didn't like sex at all.

The surveys show that wasn't the case. More interestingly, they tell the story of changing expectations about marriage and sex.

Slightly more than half of these educated women claimed to have known nothing of sex prior to marriage; the better informed said they'd gotten their information from books, talks with older women and natural observations like "watching farm animals." Yet no matter how sheltered they'd initially been, these women had—and enjoyed—sex. Of the 45 women, 35 said they desired sex; 34 said they had experienced orgasms; 24 felt that pleasure for both sexes was a reason for intercourse; and about three-quarters of them engaged in it at least once a week.

Unlike Mosher's other work, the survey is more qualitative than quantitative, featuring open-ended questions probing feelings and experiences. "She's actually asking these questions not about physiology or mechanics—she's really asking about sexual subjectivity and the meaning of sex to women," Freedman says. Their responses were often mixed. Some enjoyed sex but worried that they shouldn't. One slept apart from her husband "to avoid temptation of too frequent intercourse." Some didn't enjoy sex but faulted their partner. Mosher writes: [She] "Thinks men have not been properly trained."

Their responses reflected the cultural shifts of the late 19th century, as marriage became viewed as a romantic union, not just an economic one, and as people began to dissociate sex from procreation, says Freedman. One woman, born in 1867, wrote that before marriage she believed sex to be only for reproduction, but later changed her mind: "In my experience the habitual bodily expression of love has a deep psychological effect in making possible complete mental sympathy & perfecting the spiritual union that must be the lasting 'marriage' after the passion of love has passed away with the years."

Read more about the survey and Clelia Mosher in the Standford Alumni Magazine.

Thanks to Jennifer Ouellette for linking to this story!

When Art, Apple and the Secret Service Collide: ‘People Staring at Computers’

[Absolutely fascinating. -egg]

[longform]

When Art, Apple and the Secret Service Collide: ‘People Staring at Computers’: Kyle McDonald |

Wired |

Jul 2012

How an art project led to a visit from the U.S. Secret Service.

[full story]

[longform]

When Art, Apple and the Secret Service Collide: ‘People Staring at Computers’: Kyle McDonald |

Wired |

Jul 2012

How an art project led to a visit from the U.S. Secret Service.

[full story]

Wednesday, July 11, 2012

The Hand Cut Paper Art of Lisa Rodden

[So deliciously sensual. Yum yum yum yum yum. -egg]

[Colossal]

The Hand Cut Paper Art of Lisa Rodden:

Australian paper artist Lisa Rodden cuts, slices, and folds thick layers of white paper on top of acrylic painting that is occasionally accompanied with text. The small geometric cuts reveal windows of paint creating a strikingly precise interplay of color and shadow. You can see many more examples in her paper gallery, and if you’re in Sydney you can stop by Art2Muse gallery from August 8-21 to see it in person. (via yellowtrace)

[Colossal]

The Hand Cut Paper Art of Lisa Rodden:

Australian paper artist Lisa Rodden cuts, slices, and folds thick layers of white paper on top of acrylic painting that is occasionally accompanied with text. The small geometric cuts reveal windows of paint creating a strikingly precise interplay of color and shadow. You can see many more examples in her paper gallery, and if you’re in Sydney you can stop by Art2Muse gallery from August 8-21 to see it in person. (via yellowtrace)

Hip-hop sea-shanty

Hip-hop sea-shanty:

David Minnick is a genius. That is all.

I Can't Forget the Sea (Snoop Dogg remix)

David Minnick is a genius. That is all.

A remix of the Snoop Dogg/Kid Cudi song "That Tree". The idea for this sort of remix was born when I became aware of the great similarities between the lyrical themes of rap and the lyrical themes of pirate music (Self-aggrandizement, the quest for money and treasure, romantic view of violence, sexism etc..) In spite of this "serious" description, this remix was really just a hilarious idea that I somehow managed to finish. Enjoy!

I Can't Forget the Sea (Snoop Dogg remix)

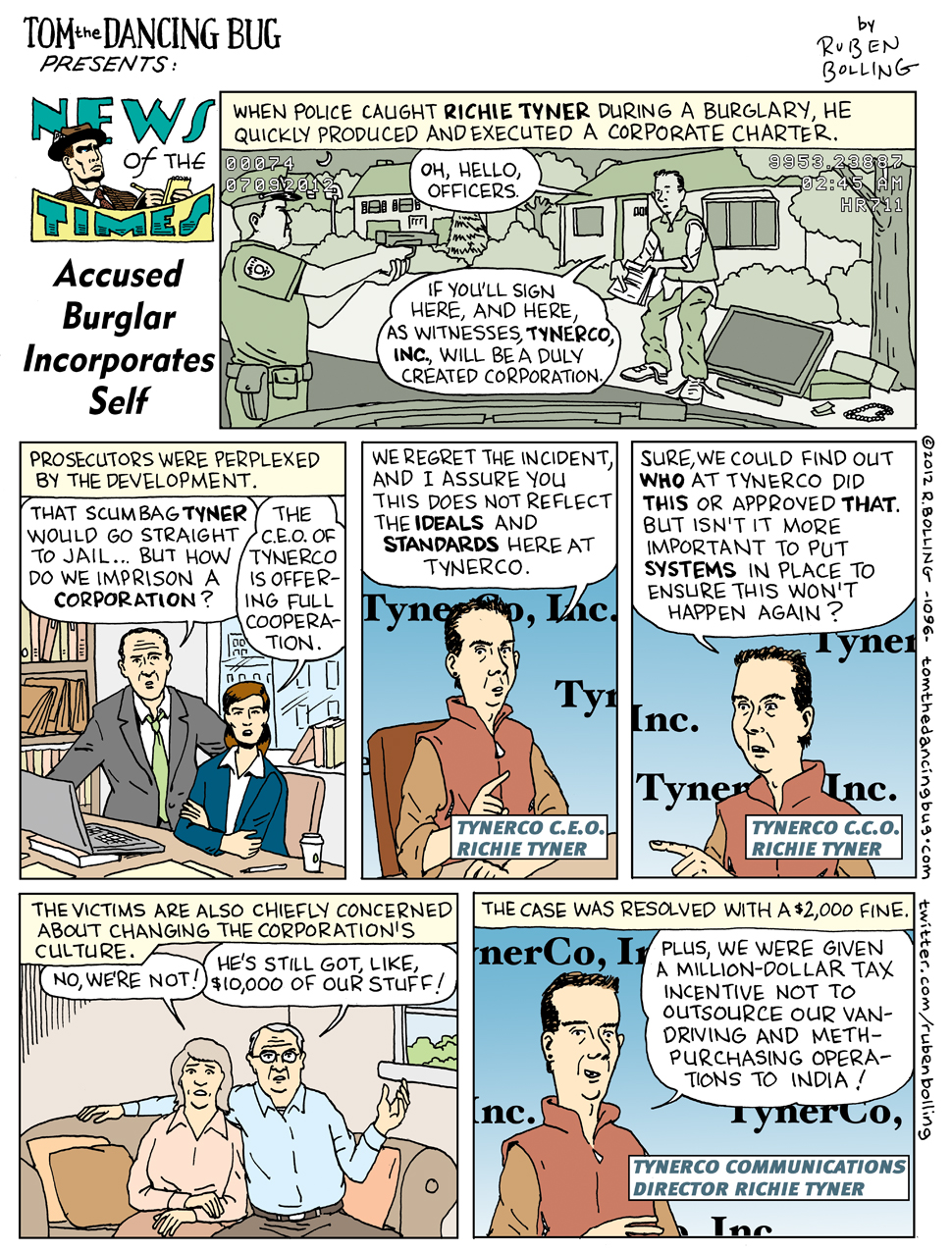

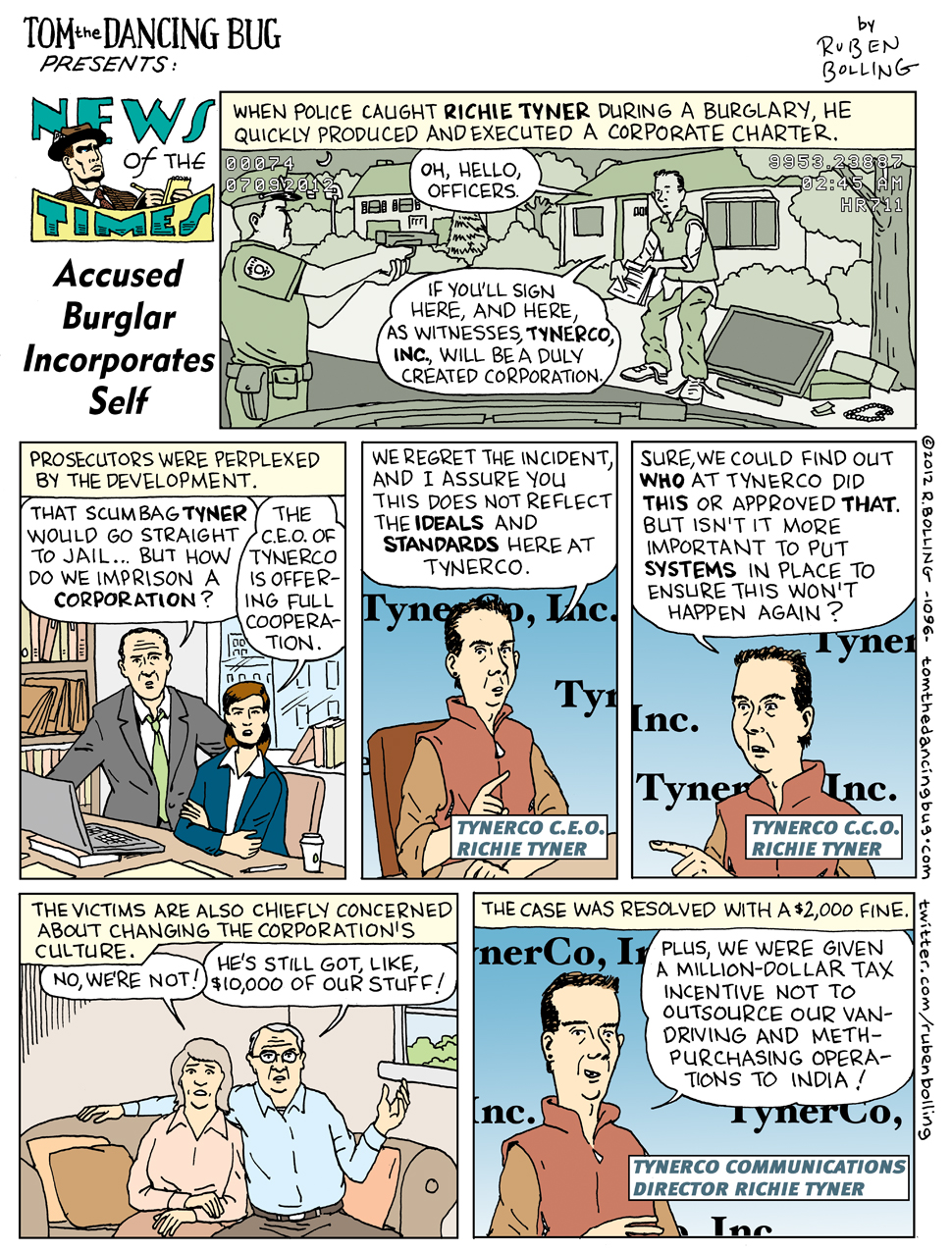

TOM THE DANCING BUG: Accused Burglar Incorporates Self

TOM THE DANCING BUG: Accused Burglar Incorporates Self:

FOLLOW @RubenBolling on Twitter.

Even better: JOIN Tom the Dancing Bug's proud and mighty INNER HIVE and receive untold BENEFITS and PRIVILEGES!

FOLLOW @RubenBolling on Twitter.

Even better: JOIN Tom the Dancing Bug's proud and mighty INNER HIVE and receive untold BENEFITS and PRIVILEGES!

Piranha used as scissors

Piranha used as scissors:

[Video Link] A man who desperately needed to cut a stick into small pieces was assisted by a kindly piranha at the Cuyabeno Rainforest in Ecuador. (Via Arbroath)

[Video Link] A man who desperately needed to cut a stick into small pieces was assisted by a kindly piranha at the Cuyabeno Rainforest in Ecuador. (Via Arbroath)

An Abridged History of Western Music in 16 Genres (cdza music video)

[Not the same 16 genres I would have chosen, but very cool :) -egg]

An Abridged History of Western Music in 16 Genres (cdza music video):

[Video Link] The latest from Boing Boing collaborator Joe Sabia's CDZA project: "an abridged history of Western Music, performing 'What a Wonderful World' in 16 different genres."

An Abridged History of Western Music in 16 Genres (cdza music video):

[Video Link] The latest from Boing Boing collaborator Joe Sabia's CDZA project: "an abridged history of Western Music, performing 'What a Wonderful World' in 16 different genres."

Higgs Boson "set to music, plays like a jaunty tango."

[BoingBoing]

Higgs Boson "set to music, plays like a jaunty tango.":

The data set which revealed the existence of the Higgs Boson may be represented as musical notation. [The Atlantic]

Higgs Boson "set to music, plays like a jaunty tango.":

The data set which revealed the existence of the Higgs Boson may be represented as musical notation. [The Atlantic]

Tuesday, July 10, 2012

Crackpots, geniuses, and how to tell the difference

Crackpots, geniuses, and how to tell the difference:

Over at Download the Universe, Ars Technica science editor John Timmer reviews a science ebook whose science leaves something to be desired. Written by J. Marvin Herndon, a physicist, Indivisible Earth presents an alternate theory that ostensibly competes with plate tectonics. Instead of Earth having a molten core and a moveable crust, Herndon proposes that this planet began its existence as the core of a gas giant, like Jupiter or Saturn. Somehow, Earth lost its thick layer of gas and the small, dense core expanded, cracking as it grew into the continents we know today. What most people think are continental plate boundaries are, to Herndon, simply seams where bits of planet ripped apart from one another.

The problem is that Herndon doesn't offer a lot of evidence to support this idea.

Herndon's book came out with the help of a vanity publishing house and Timmer uses it as an example of why peer review is important—it forces scientists with interesting ideas to actually present evidence and go through a process of answering questions about and explaining holes in that evidence. Even though peer review can be flawed, it's a much better system than not having any kind of vetting process available.

I noticed something else here, as well: The similarities in the way different kinds of badly done science often work. Even though Herndon can't present evidence supporting his theory, he can tell a good story about it. If I'm honest, the idea that, once upon a time, Earth was a gas giant is pretty appealing. As a story. It makes our planet seem more impressive. It gives a sense of a secret history known only to a few. It connects to familiar sounding things: Gas giants and Earth. And, if you don't know all the astronomical background that Timmer does, it sounds plausible.

That reminds me of something Pesco posted about recently: Creationist textbooks that teach kids that the Loch Ness Monster might be a surviving dinosaur and therefore evolution must be wrong. I learned high school biology from one of these textbooks. (In fact, that such arguments exist is one of those facts I have forgotten is not widely known information. My reaction when Pesco posted that story was to think, "Oh, right. I guess most of our readers don't know that already, do they?")

In a lot of ways, the Loch Ness Monster hypothesis is a lot like Herndon's Gas Giant Earth hypothesis. They both have storytelling appeal, especially a great sci-fi hook. They both offer access to secret knowledge. They both propose a connection between familiar ideas—a tactic that makes these hypotheses seem more accessible to lay people than the ideas they propose to replace. They both do a lot of hand-waving and mumbling when you start asking questions about the details.

I think that it can be legitimately really hard to tell the difference between science and pseudoscience. We want to know about the world around us. We often need scientific data to make useful decisions in our lives. But we can't just go out and do all the research ourselves because we have other stuff to do. We're each busy with our own area of expertise and don't have time to become experts in every question we're ever going to need an answer for. Specialization of labor is a bitch like that. At a certain point, we have to trust people who are experts in a given field to tell us what they've learned.

So how do we know who to trust?

I don't think I have a perfect answer for that, but looking at books like Herndon's and those Creationist biology texts, I have a couple suggestions:

1) If it makes a really nice story, ask for the details. (Good science usually makes a bigger deal out of the evidence than it makes out of the story. In fact, that's actually a problem many legit scientists have—they're better at talking about the details and data then they are at telling stories. But most of us respond to stories better than we respond to details and data.)

2) If the proof seems self-evident (i.e., it's just good common sense), ask more questions.

3) If believing the idea will make you smarter than the official experts, be suspicious. Experts aren't always right. But they do know their fields and experience does matter. Chances are, you're an expert in something. Say you knew how to bake pies really well. You'd be pretty suspicious if somebody who didn't bake (or didn't even really cook much) told you that you were making pies all wrong—and that they had a secret pie recipe that was better than yours. They might be right. It's worth taking a look at their evidence. But it also worth being skeptical.

4) If the studies used to prove it are really old, or if there's only a few of them, dig deeper. What looks like truth when you look at five research papers can very quickly become completely untrue when you look at 500. What sounds like a good idea when presented by it's originator can turn out to be terrible when you talk to a few other people. Try to get a sense of what the bulk of evidence is saying.

5) If you're told you can't trust any other sources of information (especially because of Big Conspiracy, or because so-and-so expert is a bad person in other areas of his or her life), be cautious. Replication is a powerful tool. It helps us get past accidental and intentional biases to see something closer to the truth. Suppressing replication is also powerful, because it leaves you with no way to check against bias.

Obviously, all these rules come with caveats. But I think they're a good place to start.

Read John Timmer's full review of Indivisible Earth at Download the Universe

Image: Cracked pot, a Creative Commons Attribution (2.0) image from bonitalabanane's photostream

Over at Download the Universe, Ars Technica science editor John Timmer reviews a science ebook whose science leaves something to be desired. Written by J. Marvin Herndon, a physicist, Indivisible Earth presents an alternate theory that ostensibly competes with plate tectonics. Instead of Earth having a molten core and a moveable crust, Herndon proposes that this planet began its existence as the core of a gas giant, like Jupiter or Saturn. Somehow, Earth lost its thick layer of gas and the small, dense core expanded, cracking as it grew into the continents we know today. What most people think are continental plate boundaries are, to Herndon, simply seams where bits of planet ripped apart from one another.

The problem is that Herndon doesn't offer a lot of evidence to support this idea.

Once the Earth was at the center of a gas giant, Herndon thinks the intense pressure of the massive atmosphere compressed the gas giant's rocky core so that it shrunk to the point where its surface was completely covered by what we now call continental plates. In other words, the entire surface of our present planet was once much smaller, and all land mass.

I did a back-of-the-envelope calculation of this, figuring out the radius of a sphere that would have the same surface area as our current land mass. It was only half the planet's present size. Using that radius to calculate the sphere's volume, it's possible to figure out the density (assuming a roughly current mass). That produced a figure six times higher than the Earth's current density — and about three times that of pure lead. I realize that a lot of the material in the Earth can be compressed under pressure, but I'm pretty skeptical that it can compress that much. And, more importantly, if Herndon wants to convince anyone that it did, this density difference is probably the sort of thing he should be addressing. He's not bothered; the idea that the continents once covered the surface of the Earth was put forward in 1933, and that's good enough for him.

Herndon's book came out with the help of a vanity publishing house and Timmer uses it as an example of why peer review is important—it forces scientists with interesting ideas to actually present evidence and go through a process of answering questions about and explaining holes in that evidence. Even though peer review can be flawed, it's a much better system than not having any kind of vetting process available.

I noticed something else here, as well: The similarities in the way different kinds of badly done science often work. Even though Herndon can't present evidence supporting his theory, he can tell a good story about it. If I'm honest, the idea that, once upon a time, Earth was a gas giant is pretty appealing. As a story. It makes our planet seem more impressive. It gives a sense of a secret history known only to a few. It connects to familiar sounding things: Gas giants and Earth. And, if you don't know all the astronomical background that Timmer does, it sounds plausible.

That reminds me of something Pesco posted about recently: Creationist textbooks that teach kids that the Loch Ness Monster might be a surviving dinosaur and therefore evolution must be wrong. I learned high school biology from one of these textbooks. (In fact, that such arguments exist is one of those facts I have forgotten is not widely known information. My reaction when Pesco posted that story was to think, "Oh, right. I guess most of our readers don't know that already, do they?")

In a lot of ways, the Loch Ness Monster hypothesis is a lot like Herndon's Gas Giant Earth hypothesis. They both have storytelling appeal, especially a great sci-fi hook. They both offer access to secret knowledge. They both propose a connection between familiar ideas—a tactic that makes these hypotheses seem more accessible to lay people than the ideas they propose to replace. They both do a lot of hand-waving and mumbling when you start asking questions about the details.

I think that it can be legitimately really hard to tell the difference between science and pseudoscience. We want to know about the world around us. We often need scientific data to make useful decisions in our lives. But we can't just go out and do all the research ourselves because we have other stuff to do. We're each busy with our own area of expertise and don't have time to become experts in every question we're ever going to need an answer for. Specialization of labor is a bitch like that. At a certain point, we have to trust people who are experts in a given field to tell us what they've learned.

So how do we know who to trust?

I don't think I have a perfect answer for that, but looking at books like Herndon's and those Creationist biology texts, I have a couple suggestions:

1) If it makes a really nice story, ask for the details. (Good science usually makes a bigger deal out of the evidence than it makes out of the story. In fact, that's actually a problem many legit scientists have—they're better at talking about the details and data then they are at telling stories. But most of us respond to stories better than we respond to details and data.)

2) If the proof seems self-evident (i.e., it's just good common sense), ask more questions.

3) If believing the idea will make you smarter than the official experts, be suspicious. Experts aren't always right. But they do know their fields and experience does matter. Chances are, you're an expert in something. Say you knew how to bake pies really well. You'd be pretty suspicious if somebody who didn't bake (or didn't even really cook much) told you that you were making pies all wrong—and that they had a secret pie recipe that was better than yours. They might be right. It's worth taking a look at their evidence. But it also worth being skeptical.

4) If the studies used to prove it are really old, or if there's only a few of them, dig deeper. What looks like truth when you look at five research papers can very quickly become completely untrue when you look at 500. What sounds like a good idea when presented by it's originator can turn out to be terrible when you talk to a few other people. Try to get a sense of what the bulk of evidence is saying.

5) If you're told you can't trust any other sources of information (especially because of Big Conspiracy, or because so-and-so expert is a bad person in other areas of his or her life), be cautious. Replication is a powerful tool. It helps us get past accidental and intentional biases to see something closer to the truth. Suppressing replication is also powerful, because it leaves you with no way to check against bias.

Obviously, all these rules come with caveats. But I think they're a good place to start.

Read John Timmer's full review of Indivisible Earth at Download the Universe

Image: Cracked pot, a Creative Commons Attribution (2.0) image from bonitalabanane's photostream

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)